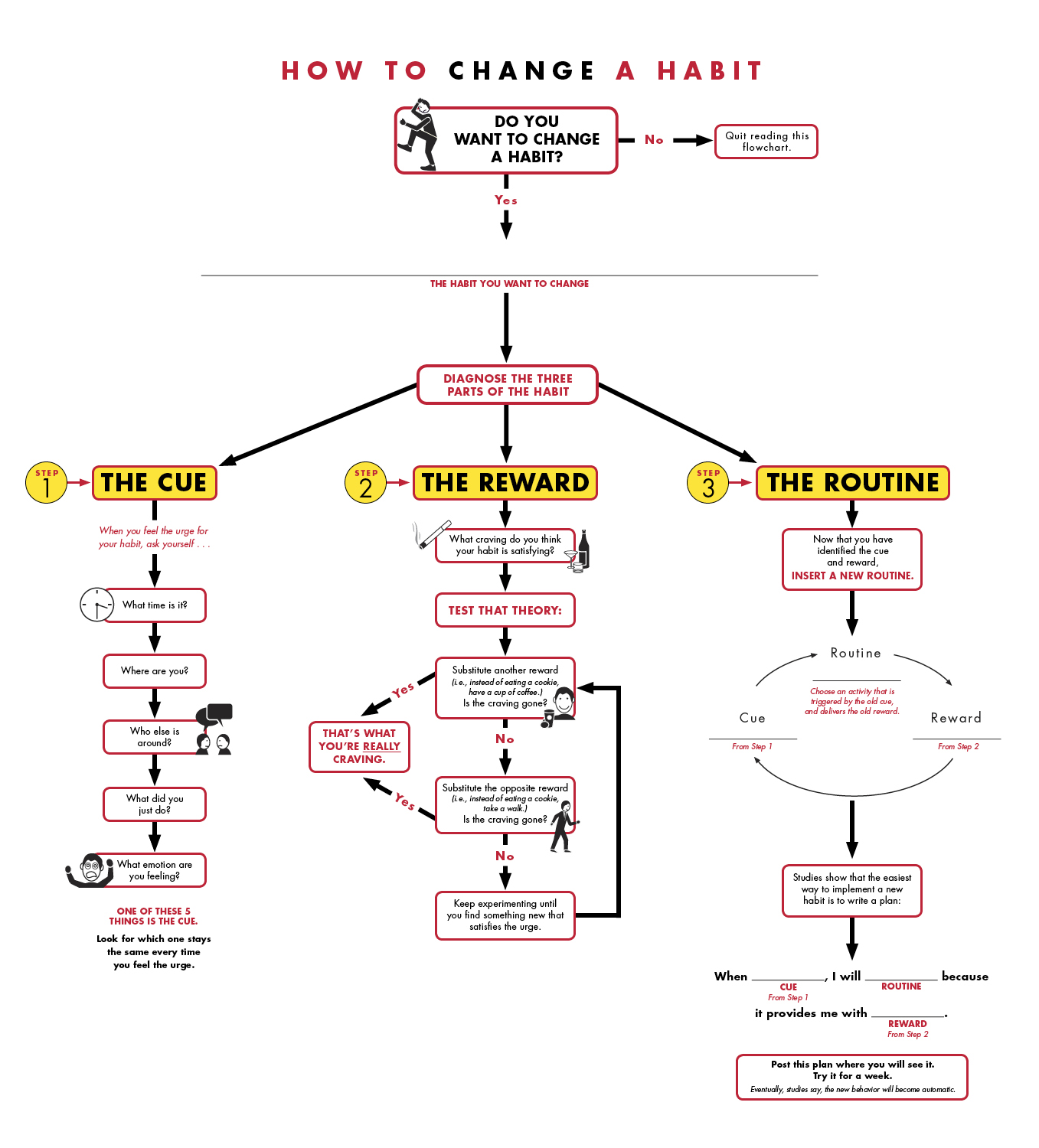

īCIs can utilise habit-formation in two ways: as an outcome, or a behaviour change technique based on promoting context-dependent repetition. Commentators have called for habit-formation to be integrated into BCIs.

Habitual behaviours should therefore be resistant to motivation lapses that can occur after an intervention period ceases. Habits guide action rapidly and efficiently, and, in associated contexts, behaviour tends to be regulated more by habit than conscious intentions. As habit forms, behavioural control is delegated to external cues, reducing demand on attention and memory processes.

Context-consistent performance reinforces the context-behaviour association, and so habits should be self-sustained beyond an active intervention period. Several characteristics make habit-formation relevant to behaviour change. This reinforces a mental context-behaviour association, to the extent that the context becomes sufficient to activate the association, which in turn triggers an impulse to perform the habitual behaviour, potentially without intention, cognitive effort or awareness. eating a banana) in a stable context (e.g.

Habit forms through repetition of a behaviour (e.g. `Habit’ refers to a process whereby environmental cues automatically activate an unconscious impulse to perform a behaviour that has, through repetition, become associated with those cues `habitual behaviour’ denotes any action controlled by this process. Habit-formation has attracted interest as a possible mechanism for behaviour change maintenance. The habit-formation model appears to be an acceptable and fruitful basis for dietary behaviour change.ĭietary behaviour change interventions (BCIs) have the potential to reduce the prevalence of ill-health and premature death, but many have only short-term success, with effects eroding over time as old behavioural patterns are resumed. Although many seemingly poorly-specified habit goals were set, goal characteristics had minimal impact on habit strength, which were achieved within two weeks for all behaviours (p’s < .001), and were maintained or had increased further by the final follow-up. Participants understood and engaged positively with the habit-formation approach. ANOVAs explored changes in habit strength, recorded at home visits and one- and two-month follow-ups, across time and goals. Thematic analysis of post-intervention qualitative interviews evaluated acceptability, and self-reported habit goals were content-analysed. Qualitative and quantitative data were taken from 57 parents randomised to the intervention arm, and so analyses presented here used a pre-post intervention design. We explored whether (a) the habit-formation model was acceptable to participants, (b) better-specified habit-formation goals yielded greater habit gains, and (c) habit gains were sustained (d) even when subsequent, new habit goals were pursued. The intervention supported parents in pursuing child-feeding habit goals in three domains (giving fruit and vegetables, water, healthy snacks), over four fortnightly home visits.

Breaking habits statistics trial#

This study used process evaluation data, taken from a randomised controlled trial of a healthy child-feeding intervention for parents previously shown to be effective, to explore the applicability to dietary behaviour change of predictions and recommendations drawn from habit theory. Forming `habit’ - defined as a learned process that generates automatic responses to contextual cues - has been suggested as a mechanism for behaviour maintenance, but few studies have applied habit theory to behaviour change.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)